Writing Fiction to Heal Demo

I want to share something special with you in this article. A real-life demo of what a piece of the writing fiction to heal process can look like. First off, I have to thank my client (whose name has been changed for anonymity) for being brave enough to let me use her situation and work here so that all of you can see how beneficial even one piece of the process can be.

Client History

My client Lila came to work with me with a specific traumatic experience in mind. When she was nine, she and her family were driving to visit her grandparents. It felt to her “like any other time we’d gone to visit” but they didn’t make it there. They were hit head-on by a long-haul truck. She was the only survivor of the accident.

Though she has years of therapy under her belt, she said that she’s “never fully recovered” from living through what took the rest of her family from her. She said repeatedly in our conversations, “I should have died with them. At least we’d all be together in a different place.” She has tried writing a memoir but felt too close to the material and was never able to finish a draft. Though she never desired to write fiction before, she came to me with a willingness to try out the process and “see if it works.”

Digging into the pre-work

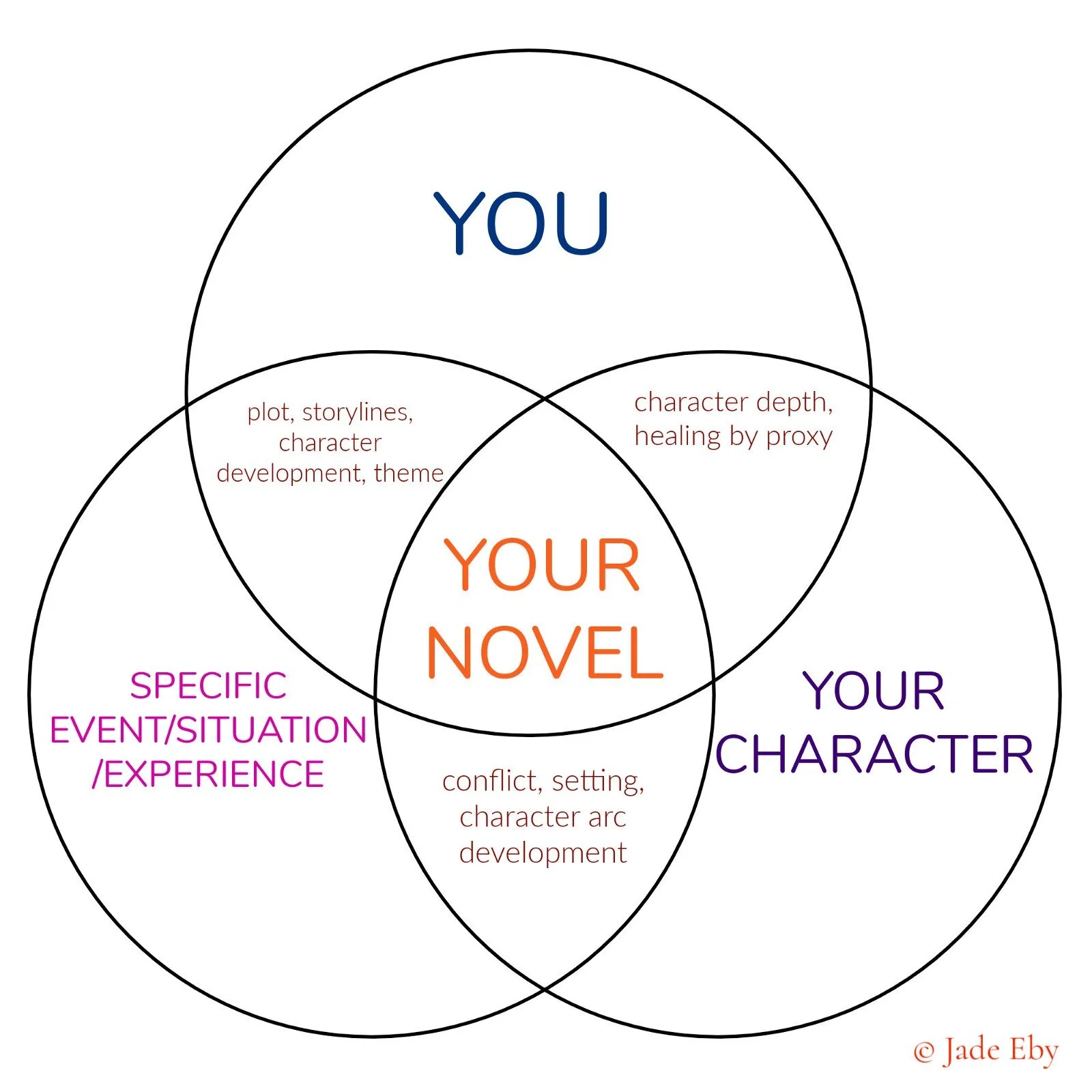

This is an exercise I start a lot of my clients with who are interested in taking a piece of their life (trauma, experiences, situations, etc) and turning it into a fictional story to help with their healing journey. It’s an easy way to get started because it’s visual and visceral — precisely because you are at the helm of the decisions.

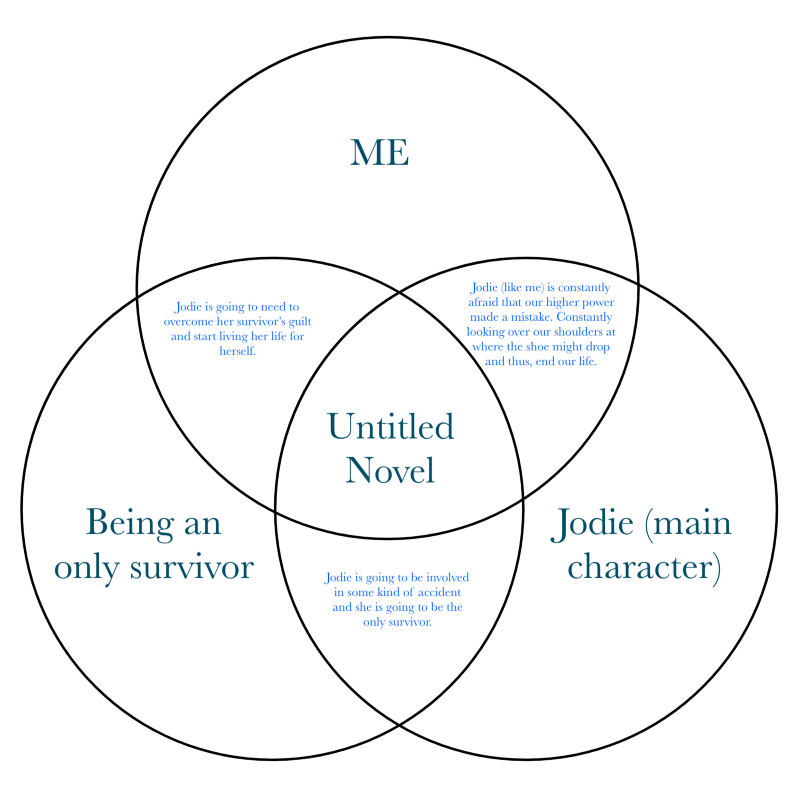

I asked Lila to fill out the four main sections of the diagram to represent her potential story. This was the result:

Lila decided she did want to explore her experience as being an “only survivor” and she decided to name her main character Jodie. This felt pretty natural to her. The next part of this exercise is where reality and fiction get to play together and be inspired by one another — and the possibilities of where you can take the novel, character, and story show up very quickly. But it can get overwhelming, too.

For Lila, she saw the possibilities of where she could take the story as too much overwhelm and it shut her down until we were able to talk through what “mashing together” the sections looked like and that having a few different ideas was actually really good! In fact, I told her that she could make a new Venn Diagram for each of her ideas to see which one felt the most burning or imperative to follow through on. Most often, the first or second time through the exercise, it’s natural to take the “reality” and dump them into the sections. I encourage that, actually. Because what happens is that once it’s down on paper (or the page), it offers us the chance to see it in comparison to other avenues.

Here are three of her completed exercises (click on the photo to see it in a larger size):

Though Lila didn’t see it at first, what struck me about all three of these exercises was that they contained the crucial elements for her healing and for her story. When she mashed “herself” vs “Jodie” — she was really speaking about how she felt, emotionally. Tapping into that self-awareness helps build real-life and dynamic characters. And in every different exercise, we see a different “part” of Jodie (or really, Lila). When she mashed the “situation/experience” with “Jodie,” she carried over her real-life conflicts. They are specific enough to Lila that she can tap into the sensory details needed to write a scene if she wanted to, but yet vague enough that any other character could “inhabit” those scenes as well. Lastly, when she mashed “situation/experience” with “herself,” she tapped into the changes she wanted most wanted to see within herself. A desire to overcome her survivor’s guilt. A desire not to be the face of a movement. A desire to free herself from the deep anger she’s kept locked inside.

Now, the kicker is — all of this was done without her really knowing that’s what she was doing. It wasn’t until we broke it all down that she realized she actually DID feel those things, she just hadn’t verbalized it. Her subconscious knew what she needed to know, even if she didn’t consciously know it. This is the power of thinking in terms of fiction writing — it opens up a dam in us that we may not have been able to access before.

Putting it into action

I challenged Lila to then take all three of her exercises and write a different scene for each one using the “mashup” section as a jumping-off point. I asked her to try and keep the two other sections in mind as she wrote the scenes. What happened? This is what she said to me in an email response after finishing two of the three scenes:

I attempted the most “familiar” scene first — of her surviving an accident and it took me five hours to get a single paragraph. It was so hard and I wanted to quit because everything I wrote felt wrong. But the second scene, I basically took a conversation that happened in real life and rewrote it the way I wanted it to happen and it felt so… liberating. I made Jodie use words I wanted to say but never did. Like when she is talking to Jeff and tells him to fuck right off because he doesn’t know what it’s like. OMG! I’ve wanted to say that to so many people but never had the courage to. This has made me both excited and nervous to write the third scene. I’m terribly afraid of my own anger so I don’t know what this will look like.

As a coach, this response touched me because I know, personally, how hard it is to write that scene. The one that’s nearest and dearest to your heart. And I know that sometimes it can’t be written because we’re not there yet. Lila wasn’t ready to write about her situation in a direct way. That’s why the second scene felt more appealing to her. There was less of an emotional charge, still a modicum of reality, but a lot more of what she wanted to explore. I was pleased and proud that she bravely put herself out there to try. Many people won’t ever allow themselves to get that far. But it was the third scene that blew us both away. Here’s an excerpt she graciously allowed me to share:

Holly stared at me, probably waiting for an apology that I couldn’t give her. I knew she wanted me to say something, anything to make her feel better but there was nothing left to say after my explosion.

“You know,” she said, picking up her purse from beside the couch. “You’re a really shitty friend. I’ve tried my hardest to be there for you. I’ve tried to be understanding and supportive, but I’ve had enough. You don’t actually care about me or my feelings. All you want to do is sit and rehash your old shit, over and over again.”

I’m furious. Because she’s right. But also how could she understand? That’s the problem. She can’t. She doesn’t know the first thing about my situation other than what I’ve let her in on. Everyone seems to forget that they didn’t have to go through it. I did.

“Fine, I’m a shitty friend,” I said back. “So just go then. Pick up your shit and go.”

She stared at me for a few more seconds.

“GO!” I screamed. “Get the fuck out of my apartment!”

She winced at the harshness in my voice but moved to the door. She looked back at me once and then closed the door, not even bothering to slam it.

I wished she’d have slammed it. Then I could be angry at her instead of feeling the familiar rise of self-loathing engulfing me.

Out the window, I watched as she got into her car and drove away. Probably the last I’d ever see of her. Yet another person who couldn’t handle me. I’m too much. I’ve always been too much. And I probably always will be.

Everyone’s always leaving me when I need them the most.

When I asked Lila about this scene, she said that it came out the quickest of the three scenes. That it “flowed” right through her. I asked her why she thought that was the case and her answer stunned us both: “Because this is how I’ve felt my entire life and didn’t know it until I wrote it.”

Even though this is one tiny piece of the overall fiction novel process, it was an incredible breakthrough for Lila. She was able to literally see how her reality and the fictional scene she’d written came full circle. She was able to tap into an emotion that she’d pushed down for years and brought it to the surface. Not just for the scene, but for herself, too. In writing this scene, she allowed herself to be vulnerable and she was rewarded with a piece of self-awareness she hadn’t brought into the light until then.

When I asked her how she felt re-reading the scene she said, “I feel like a mixed bag of emotions. On the one hand, I’m sad because I realize that I am angry. I’ve been angry. But it’s never felt appropriate to show it. On the other hand, I feel… hopeful. I didn’t really know what was living in me and now it’s starting to show. That’s exciting but scary.”

She’s absolutely right. It is scary. But it can also be liberating and exhilarating to finally release your whole self. Lila and I still have a lot of work to do, but it’s her willingness to show up, even when it’s hard that makes her healing journey worthwhile. Her desire to explore what’s hidden in the depths of her psyche through fiction writing is brave and courageous and that’s exactly what she will bring to the page, too. I believe in her capacity to take her pain to the page and turn it into something that will help her heal.

I believe everyone deserves that, too.

• • •

Did you love this and want to learn how to write fiction to heal yourself? I’ll be relaunching the official Writing Fiction to Heal Workshop soon! Sign up to be notified when it launches!